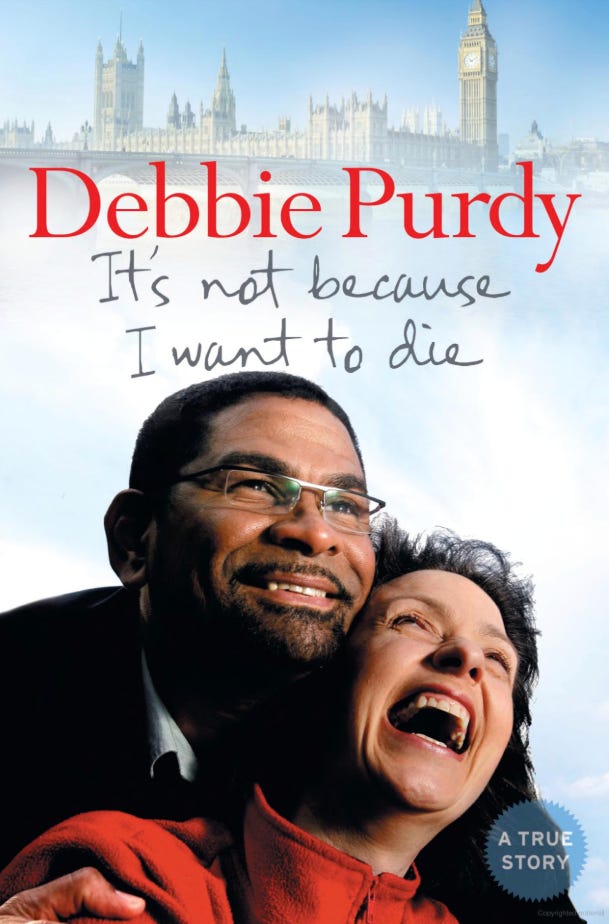

(Dobbs) “It’s Not Because I Want To Die.”

“It’s a choice between a painful prolonged and difficult death or a death that we are in control of.”

“When my life no longer is able to offer me a reason for living, I want to be able to terminate it.”

Debbie Purdy, who already had suffered for a decade and a half with multiple sclerosis, said that to me 16 years ago at her small flat in Manchester, England.

The MS ate away at her strength, at her eyesight, at her independence. What weighed on her wasn’t that she had just a short time to live. What weighed on her was, she might have a long time to live. “For a lot of us it’s not a choice between life and death,” she grieved in my story about her fight to legalize assisted suicide in the United Kingdom. “It’s a choice between a painful prolonged and difficult death or a death that we are in control of.”

She wasn’t in control of her own. Although she wasn’t ready yet, she knew that when the time came that her life would be insufferable and she’d want to end it, physically she would be incapable of doing it on her own. When I met her, she already was. Her husband was willing to help her, but under the law in the U.K., anyone “aiding and abetting” someone else’s suicide would be subject to a jail sentence of as long as 14 years. Aiding and abetting even meant the simple act of helping someone travel to Switzerland, the one country at the time that allowed assisted suicide. Just pushing her wheelchair onto an airplane at the airport in Manchester could land Debbie’s husband behind bars.

As a part of the story, I went to Switzerland to see how they did it, to the one place on earth where, no matter where someone comes from, they can get help killing themselves. The only limits are that whoever helps them cannot do it for personal or financial gain, or what Swiss law calls “selfish motives.”

The facility, in a modest building just a short drive out of Zurich, is called Dignitas, which is Latin for “dignity.”

Its sole purpose is to help people take their own lives. Whoever comes is given opportunities to change their minds before the final act, but if they say no, they are given a potion of poison in a drink, a high dose of sodium pentobarbital. It puts them to sleep, then puts them out of their misery.

Dignitas doesn’t even call it “assisted” suicide. They call it “accompanied” suicide. The philosophy behind it, the director told me, is, “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness here include the right to die. When you want, and where you want, and with whomever you want at your side.”

Also, for the reasons you want. You don’t have to attest to a terminal illness. You only have to attest to a terminal quality of life. Like Debbie Purdy’s.

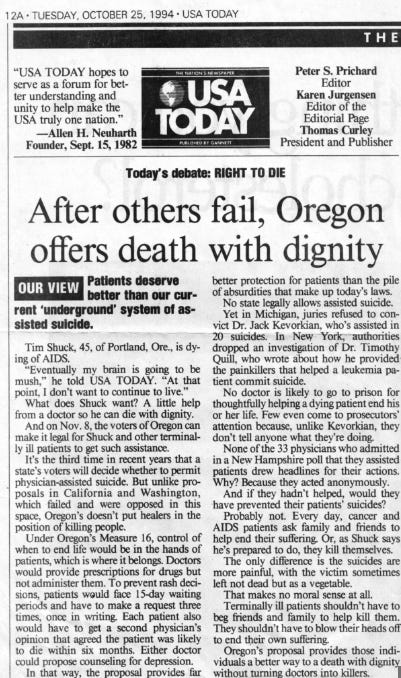

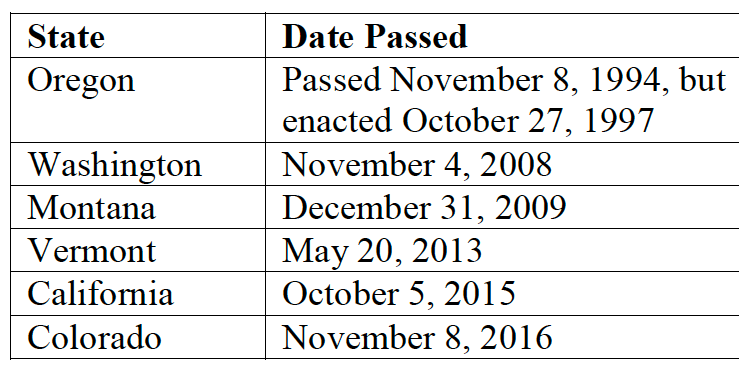

Parts of the United States were ahead of the United Kingdom. I did a story in the mid-1990s in the state of Oregon, the American pioneer in permitting assisted suicide. Oregon’s law required physicians’ testimony that a patient suffered a terminal illness— most often it was cancer— and had no more than six months to live. It also had strict regulations about who qualified for the right to die, and who didn’t. But if ending our lives on our own terms is a human right, although it still wouldn’t have helped a woman like Debbie Purdy, then Oregon’s law was a big leap forward.

Until then, suicide itself, let alone aiding and abetting, was considered a crime in most of the country.

The purpose of legal assisted suicide hit home for me when I interviewed three citizens in Oregon’s capital, Salem, before the law passed. Two were a married couple and she had an agonizing illness, not unlike Debbie Purdy’s in England. She no longer wanted to live. Her husband collected plastic bags from the dry cleaner, she took sleeping pills, and put the bag over her head. It didn’t work. It was just another hellish chapter in her suffering. The third was a man whose son had an incurable and incapacitating neurological disease. In the end, unable to get help to die peacefully, he starved and dehydrated himself to death.

Passing laws to help people kill themselves, no matter how compassionate, can be a tough call. On the one hand, if someone’s suffering unbearably but can’t kill themselves alone, why should the state say someone else can’t help them die? On the other hand, at what point does compassion amount to murder? The question opponents of these laws ask is, when does man become God? And where do you draw the line between someone with a terminal illness, someone with an unbearable but survivable condition, and someone who’s depressed over a business gone bankrupt or a love affair gone bad?

Right now, with a variety of requirements and restrictions, eleven states and the District of Columbia permit assisted suicide. One of them is Montana, where 26 years ago they made it a constitutional right.

I interviewed the head of the Montana Medical Association when the debate there was still going on. If a bill passed, doctors would be a compulsory part of the process. His view was, it’s a violation of the Hippocratic Oath to make physicians act as “executioners” to their patients. What’s more, he was an oncologist, and told me he couldn’t count the number of patients he had concluded had less than six months to live, but then they surprised him.

The contrary point of view was, compassion is a human hallmark, and death is a human right.

Finally, Great Britain— specifically England and Wales—is coming to that same conclusion. Until now, although suicide itself had been decriminalized, assisted suicide hadn’t. But this year the House of Commons approved the “Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill.” It would allow citizens to help people kill themselves after getting consent from two doctors, a psychiatrist, a social worker, and a legal expert. Interestingly, the U.K.’s political parties allowed it to be what they call a “conscience vote,” which means parliamentarians are allowed to vote their conscience rather than any party line. It is in the final stages of passage and will take effect four years from now. It will be cumbersome, but it is a step forward.

Just not soon enough for Debbie Purdy.

In 2010 she wrote a book called, “It’s Not Because I Want To Die.” She had become the most outspoken campaigner for an assisted suicide law in the U.K. As she said in an interview with the BBC, “It’s not a matter of wanting to end my life, it’s a matter of not wanting my life to be this.”

But it was. In 2014, she went into hospice and starved herself to death.

However, in a few years, thanks to her, others won’t have to end it like that.

Over more than five decades Greg Dobbs has been a correspondent for two television networks including ABC News, a political columnist for The Denver Post and syndicated columnist for Scripps newspapers, a moderator on Rocky Mountain PBS, and author of two books, including one about the life of a foreign correspondent called “Life in the Wrong Lane.” He also co-authored a book about the seminal year for baby boomers, called “1969: Are You Still Listening?” He has covered presidencies, politics, and the U.S. space program at home, and wars, natural disasters, and other crises around the globe, from Afghanistan to South Africa, from Iran to Egypt, from the Soviet Union to Saudi Arabia, from Nicaragua to Namibia, from Vietnam to Venezuela, from Libya to Liberia, from Panama to Poland. Dobbs has won three Emmys, the Distinguished Service Award from the Society of Professional Journalists, and as a 39-year resident of Colorado, a place in the Denver Press Club Hall of Fame.

You can learn more at GregDobbs.net

Beautiful and necessary essay. Thanks Greg.

Many of us have had to help a beloved dog or cat out of the end of life's misery. It is a bittersweet moment where compassion overrides the longing to extend the selfishness of extending misery. We all have the ability to simply stop eating and drinking should we get to the point where all hope of recovery is gone.