(Dobbs) Superpowers Stiff The United States

A redistribution of power in the wrong direction.

It is a milestone month and particularly, as of Monday night in Moscow, a menacing week in superpower history. For the United States of America, not in a good way.

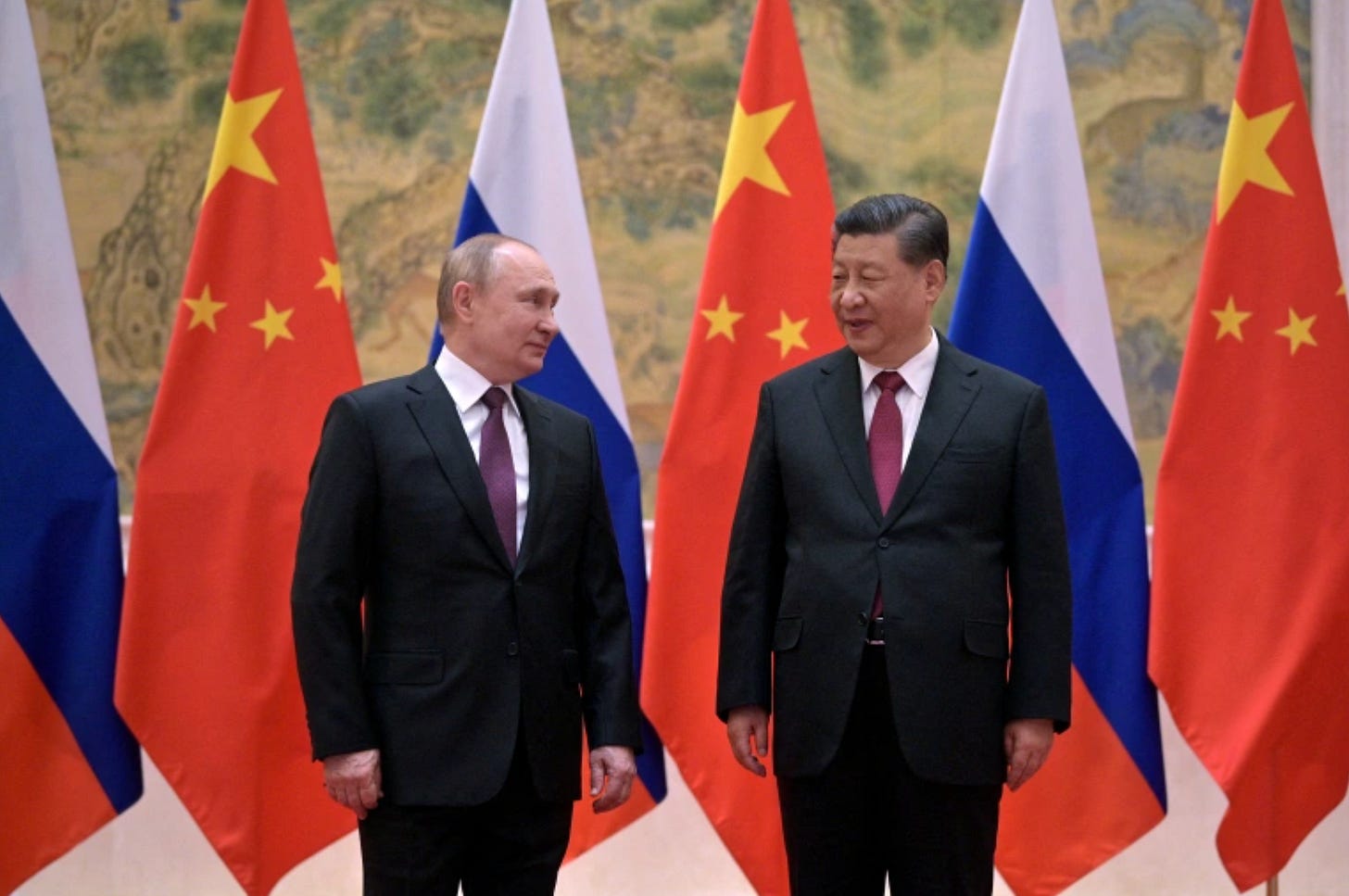

Just two-and-a-half weeks ago at the Olympics in Beijing, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping all but held hands as they declared in a joint statement, “Friendship between the two states has no limits, there are no forbidden areas of cooperation.”

That’s a friendship between two totalitarian leaders, each with no respect for democracy, with animus toward America, and with an arsenal of nuclear weapons.

It makes me mindful of the maxim I heard so often in the Middle East over the years about rivalries and alliances: “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

They see us as enemies because, by the yardsticks of competition, influence, and ideology, we butt heads with China (despite relationships in trade and diplomacy), and with Russia. So Russia and China, traditionally wary enemies themselves but eager to confront their common foe, have forged this new friendship. It might be a marriage of convenience— chances are that each will be watching for the other to cheat on it— but their statement asserted, ominously for the United States, an “increasing interrelation and interdependence between the states” and trumpeted that “a trend has emerged towards redistribution of power in the world.”

That’s not far off the mark.

Thirty years after the Soviet Empire crumbled, Russia is back on the world stage. Still poised to attack Ukraine from three sides— with its border forces continuing to grow, despite its duplicitous dispatches about departing troops— Vladimir Putin looks like he’s on the verge of not just reinforcing Russia’s regional orbit but now, of expanding his borders by force. Especially because he just made a zealous nighttime television address to his nation about Ukrainians “who are tied up with us in family and blood ties,” warned of “the possibility of a continuation of bloodshed” there, then said he was formally recognizing the independence of and sending troops to occupy two Ukrainian territories currently controlled by Russian-speaking separatists.

That might be the pretext for the even bigger invasion that Western analysts have foreseen.

Meantime, it was exactly fifty years ago yesterday when President Richard Nixon traveled to China after its decades in diplomatic isolation and came face to face with what Napoleon once called the “sleeping giant.”

At the time, it was still a rural nation caught in the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Today, it is an economic powerhouse, second only to the United States and, in a number of ways, already past or poised to surpass us. Militarily, China has two aircraft carriers with more being built, a fleet of warplanes to be reckoned with, and the world’s largest army. It has replaced Russia as the second most powerful military force on earth.

The giant sleeps no more. Both China and Russia, to use a cliché, are sowing their oats.

It’s a challenge to the U.S. on several fronts.

If Putin does overpower Ukraine in the guise of cultural reunification and secure Russian borders, what’s the chance he’ll have his eye next on other nations along its boundaries that once were part of the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence: Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan? Even Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, which are democracies (if sometimes deeply flawed) and members of NATO?

China, meantime, has asserted itself more aggressively than ever before, challenging longtime American supremacy in the South China Sea and last month even sending warplanes to overtly overfly two U.S. aircraft carrier groups as they patrolled waters near democratic Taiwan, which China claims as its own.

At the same time, once-democratic Hong Kong is ever tighter in China’s grip.

Democracy may be a high priority for the United States, but it certainly isn’t for the other two superpowers. One of Vladimir Putin’s close advisors once told me in Moscow what democracy meant in his country: “A system designed to undermine the leadership.” Both Russia and China align themselves with other authoritarian governments, and imprison citizens who challenge their undemocratic governance. In that joint statement from Beijing, they declared that “democracy is a universal human value” but at the same time said, “It is only up to the people of the country to decide whether their state is a democratic one.”

All of which spells a weakening of America’s power and influence on the world stage.

Some in our nation say good riddance to being the world’s policeman. It has sometimes been painful and costly and I too wish that we didn’t have to do it, but look at the world if we weren’t. Nations historically in Russia’s crosshairs— Ukraine first among them— might long since have been sucked back into its sweep without a fight. Taiwan might long ago have been absorbed by the People’s Republic of China, and Hong Kong might already have lost the liberties its people still have.

The U.S. is doing what it can. But according to think tanks that track democracy worldwide, authoritarianism is on the rise— even in nations allied with the West like Hungary and Poland, Turkey and Vietnam— while democracy is deteriorating. Although we have not modeled the best democratic ideals ourselves for the past few years, the best we can do now is lead by example or even, if circumstances warrant, fight to preserve a world in which democratic values are cherished.

But given the new superpower partnership— the “redistribution of power in the world” that China and Russia propound— there is no guarantee that we shall preserve what we’ve had. The world will change, with or without us.

Over almost five decades Greg Dobbs has been a correspondent for two television networks including ABC News, a political columnist for The Denver Post and syndicated columnist for Scripps newspapers, a moderator on Rocky Mountain PBS, and author of two books, including one about the life of a foreign correspondent called “Life in the Wrong Lane.” He has covered presidencies and politics at home and international crises around the globe, from Afghanistan to South Africa, from Iran to Egypt, from the Soviet Union to Saudi Arabia, from Nicaragua to Namibia, from Vietnam to Venezuela, from Libya to Liberia, from Panama to Poland. Dobbs has won three Emmys, and the Distinguished Service Award from the Society of Professional Journalists.