(Dobbs) Jimmy Carter: If Not Our Best President, One Of Our Best Men

“I am in a unique position: I’m a former president of the United States of America. Wouldn't it be a pity to waste that?"

Jimmy Carter will not be remembered in the pantheon of our best presidents. Taxes and interest rates went sky-high, and we lost Iran. But periodically I reported on him— before his presidency, during his presidency, and after his presidency— and I’m convinced that he should be remembered as one of our best ex-presidents. He should also be remembered as one of our best men.

I want to tell you why.

The first time I linked up with Jimmy Carter, it was 1975, wintertime in Iowa, and he was campaigning for president. He was a southern-talking one-term governor from a Deep South state. He was going up against the last surviving icon of a political dynasty, Ted Kennedy. Nobody thought he had a prayer of winning the 1976 Democratic nomination, let alone of going on to knock off the incumbent president Gerald Ford.

Nobody except Jimmy Carter.

As a young producer for ABC four years earlier, I already had covered presidential campaigns when even in the early stages, candidates chartered 727s and traveled with a coterie of aides. But my lasting visual from the first time I covered Carter is of him getting off a small propeller aircraft, carrying his suit bag over his shoulder with just two aides in tow. He held small coffee-klatches in the homes of local Democrats. He sometimes slept in their spare bedrooms. It was not just a grass-roots campaign, it was funded on a shoestring.

His campaign continued on that track for a long time until people began to see, maybe this guy has a chance. It had to be humbling, but he was a humble man.

Then when Carter won the White House, he saw an opening for American diplomacy in the Middle East that might bring peace between Israel and Egypt, who had fought three vicious wars since the creation of Israel. He rushed into that opening. I shuttled around the Middle East with the president, not just between Israel and Egypt but to other Arab capitals of influence in North Africa and the Persian Gulf. He was tireless, he was relentless. Eventually, he won what he fought for, something no president before him had achieved: a handshake and a signature between once bitter enemies, Israel’s Menachem Begin and Egypt’s Anwar Sadat.

The peace of the Camp David Accords, however strained it has sometimes been, has lasted to this day, and the sentiment that came from both Begin and Sadat— both of whom at different points wanted to walk out of the negotiations— was, it wouldn’t have happened without the dogged determination of Jimmy Carter.

I didn’t see him again until his ex-presidency, some 25 years later, when I went with a camera crew to Liberia, on the coast of West Africa, to cover the first presidential elections there after a 15-year-long civil war that had left Liberia in disarray and in ruins.

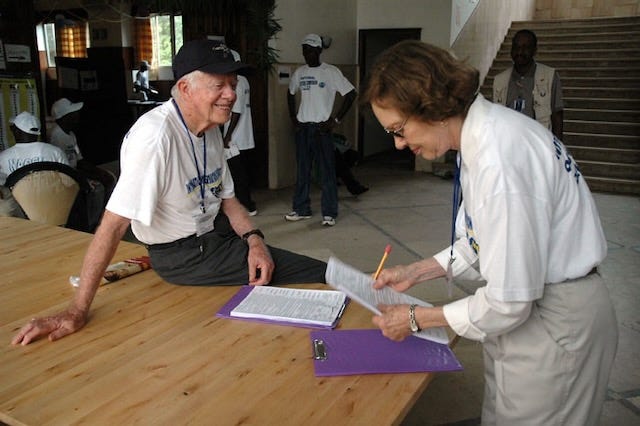

In its role as a conflict mediator, the ex-president’s Carter Center had established the framework for a free and fair vote, and Jimmy Carter and his former First Lady Rosalynn came to see it through. One of the first things Carter did when he got there, after traveling commercially for 36 hours from Atlanta, was meet with the two leading candidates and convince them that democracy could take root.

What Carter told me in an interview when we were together there was, “You can’t force democracy on other people. You have to give them an opportunity to define their own standards of democracy and their procedures for reaching a democratic government.” His force of personality was strong enough that when the two leading candidates met— a 38-year-old soccer legend with no political background and a grandmother and former finance minister— they shook hands, they smiled, and they chatted. After 15 years of brutality from border to border, there was none around the election.

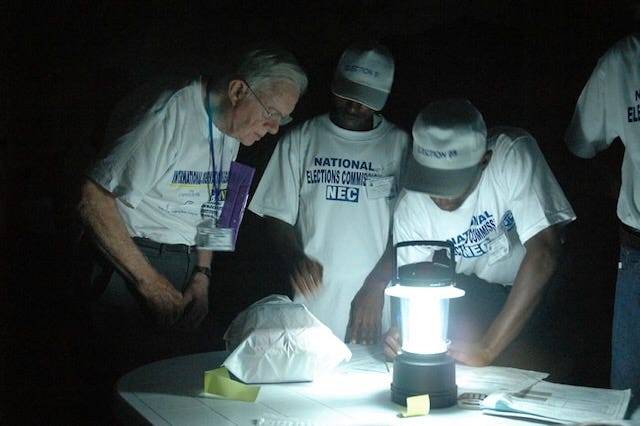

What Carter preached was ballots, not bullets, and it was persuasive enough that on election day itself we saw people who traveled all night, some in bare feet, then stood for hours in long lines, to vote. Some had been there since midnight: people with no legs, people who couldn’t see, women with little babies on their backs.

We spent part of that day with the Carters themselves as they went from cinderblock polling place to cinderblock polling place, the ex-president’s humility showing yet again.

He was acting as a poll watcher, sporting a baseball cap with a clipboard in his hands and pencil on a string around his neck. It was hot and humid and the voting sites were packed with people at every stop, but to the chagrin of the Carters’ small and less-than-thrilled Secret Service detail, they cut a path straight to the lines of voters on rocky hillsides, to monitor and confirm that all the electoral rules were being followed. This was Jimmy Carter, once the most powerful man on earth, but he didn’t demand a protective path eight feet wide, he didn’t require a red carpet, he didn’t have anyone holding an umbrella or waving a fan to mitigate the African sun.

A little anecdote: after the first couple of stops, I came out perspiring from head to toe, but Carter was dry as a bone and I asked him how it was that the heat and humidity didn’t get to him. His answer was, “Son, I’m from Plains, Georgia. This is just like home.” After maybe the fourth voting place though, Carter came out drenched with sweat and walked up to me and said with a smile, “You happy now?”

I was so impressed with how Carter handled himself— flying across many time zones to an equatorial nation where both water and electricity were still in desperately short supply, where neither decent hygiene nor surefire security was guaranteed, and whose civil war hadn’t even entirely ended— that I asked if I could come down to Georgia and do a long interview with him when we all got home. A couple of weeks later, I did, and when he answered a couple of my questions, I knew that when I decided that despite his often-plagued presidency he was a great man, I wasn’t wrong.

This was the first question (since I had previously seen him on a similar mission in Venezuela): “You’ve participated in so many operations like the one in Liberia. And watching you it was hot, it was muggy, it’s dirty, it’s dysfunctional, it’s not the safest place on earth. You could be living the easy life. Why not?”

This was Carter’s answer: “Well it’s not a sacrifice for me. It’s a very gratifying experience. It’s exciting, it’s challenging, it’s unpredictable, it’s adventurous. And the culmination in the case of a destitute and bereaved and suffering country like Liberia of a successful election followed by an enlightened administration is an extremely worthy personal goal for me, and I hope and expect that’s what we can see. It’s been by far the best part of my life.”

But I still wanted to know why he didn’t feel entitled at his age, and after all his work, to just sit in a rocking chair on his front porch in Plains and relax. What he said sticks with me to this day, and it went pretty much like this: “I am in a unique position: I’m a former president of the United States of America. If I see a problem anywhere in the world, I can call a prime minister, a potentate, another president, and at least have a chance to be heard. Wouldn’t it be a pity to waste that?”

Other former presidents have. Jimmy Carter never did.

Over more than five decades Greg Dobbs has been a correspondent for two television networks including ABC News, a political columnist for The Denver Post and syndicated columnist for Scripps newspapers, a moderator on Rocky Mountain PBS, and author of two books, including one about the life of a foreign correspondent called “Life in the Wrong Lane.” He also co-authored a book about the seminal year for baby boomers, called “1969: Are You Still Listening?” He has covered presidencies, politics, and the U.S. space program at home, and wars, natural disasters, and other crises around the globe, from Afghanistan to South Africa, from Iran to Egypt, from the Soviet Union to Saudi Arabia, from Nicaragua to Namibia, from Vietnam to Venezuela, from Libya to Liberia, from Panama to Poland. Dobbs has won three Emmys, the Distinguished Service Award from the Society of Professional Journalists, and as a 38-year resident of Colorado, a place in the Denver Press Club Hall of Fame.

You can learn more at GregDobbs.net

Was he too good to be President? That says more about us than it does about him.

Jimmy Carter Dies at 100

••••

An Open Letter to President Jimmy Carter

Dear President Carter,

In a time when the words “Christian values” are often wielded as weapons by those who seem unfamiliar with their essence, your life remains a testament to what they truly mean: love, humility, service, and unyielding moral courage.

As the 39th President of the United States, you brought a quiet dignity to the Oval Office, pursuing peace where others stoked conflict. Your leadership in brokering the Camp David Accords showed the world that diplomacy, grounded in faith and principle, could triumph over cynicism and division. And while history has recognized your presidency more kindly with each passing year, it is your post-presidency that stands as the gold standard of what an ex-president can and should be.

From eradicating diseases to building homes for those in need, your work with the Carter Center and Habitat for Humanity has been an unparalleled legacy of compassion. You didn’t retreat to a gilded life of grift and spectacle but chose instead to labor humbly, embodying your spiritual call to serve “the least of these.”

In an era defined by loud self-aggrandizement and moral bankruptcy—where some falsely claim your faith while trampling its core tenets—you are proof that decency is not weakness and that true greatness lies in the quiet, steadfast work of lifting others up.

Thank you, President Carter, for showing us what goodness looks like.

Rest in Peace.

Sincerely, A Grateful Admirer

https://substack.com/@patricemersault?utm_source=user-menu